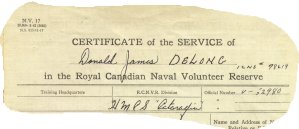

Basic Training - by Ron Graham [See

an example of the RCNVR

Record of Service document, which is the personnel record kept by

the Department of National Defense for each member of the service. - 980

Kb PDF file]

Basic training in the navy was an experience, a moulding process, a cauldron into which an unsuspecting cross section of humanity drawn from all walks of life entered in innocence, passed through in a mixture of wonderment and bewilderment, and came out of changed forever in their approach to the future.

|

Draft of new recruits arrive at muddy Cornwallis training facility. These future seamen have no idea what is in store for them this day, and every day for the next five weeks. (G. J. Gaudet DND National Archives, Ref.# DB-006-1) |

| Don Delong reports that those exiting on the other side of the train sank into knee deep mud in March 1943, which was then carried into the barracks on footwear, where it was cleaned up by uncooperative recruits. These recruits were termed "Blacklist Men" who were being punished under a "Number 11". | |

Cornwallis Today showing the H shaped barracks.

Each joined the Navy with some vague notion that it had something special to offer that would make volunteering for service in the armed forces truly meaningful. In retrospect, and with the mellowing of fifty years, no one seems quite prepared to say just what prompted the idea; nor does it matter. We are the survivors of an era.

We came from large cities, small towns, country villages; from industry, or fresh out of school, or from the prairie farm. Most had limited travel experience, little first hand knowledge of the world beyond their own community, and no experience with being a number in a vast conglomerate. We signed on with the Navy at such Reserve Divisions as HMCS Tecumseh, Queen Charlotte, Malahat, Star, Montcalm, Queen, Unicorn, Brunswicker, Chippawa, or at whatever unit was closest to home.

After signing on, having the medical, the uniform issued, you found yourself on a train taking you hundreds of miles away to HMCS Whatever to begin this new life. The train trip gave everyone plenty of time to look back upon the wisdom of their choosing to "join up". We had those quiet moments of reflection, looking about, anxiously, wanting to be one of those seemingly happy and self-assured people around you. Only later would you know they, too, were apprehensive and feeling the first twinges of homesickness.

When the train arrived at its destination you struggled onto the platform burdened with hammock and kit bag and whatever surplus luggage you foolishly thought necessary to have. Immediately there was chaos. People in authority were everywhere, all yelling at once, calling rolls, mispronouncing names, suddenly selecting out some poor individual who was slow to respond, or who had his hat on the back of his head, or forgot to say "sir", and dressed him down in the awful silence that would make his embarrassment complete.

Everyone soon recognized there was some degree of safety in numbers, that to ask a question invited derision, that there was evidence you were in a marginal no-win situation. Instinctively, self-preservation became a priority. "Home" for the next five or six weeks would be some great barn of a place filled with rows of steel bunks. If you were lucky they were two-deckers; some were three-deck monstrosities that demanded mountain climbing experience to achieve the upper level. There was a scramble to secure bottom bunks, though it later proved to be a bit hazardous when the man above climbed down searching for a footing below. Like everything else now, it became a mad rush to adapt.

There was a new language to learn. On the first day of parade training, following a late arrival the night before, too late for a meal and too late to get more than four hours sleep, some idiot would come yelling "wakey-wakey" down the rows of bunks adding "hands to breakfast" on his way out. Pandemonium reigned those first few days. No one bothered to tell you where the washrooms (heads) were, or where you were supposed to eat, and of course when you did find out, it was too late to avail yourself of either, for the instructor was yelling "fall in for divisions", whatever that was supposed to mean. Of course you were late, and soon found out that each day began with inspection, and you'd failed to shave, brush your uniform, polish your boots, etc., etc., and you were promptly subjected to dire threats of a quick departure from this world. Somehow you learned to get all of these things done, and on time, though there never seemed enough of that to go round. Sleep was hard to come by; just as you'd doze off, the top bunk resident had to go to the heads, or on watch, or whatever necessitated his stepping on your face on the way down. When sleep returned it seemed only a moment 'til someone was shaking you to go on the morning watch, and you spent the rest of the night pacing back and forth. On to the parade square you marched and wheeled and turned, frequently in the wrong direction, bringing down grave questions on the degree of your intelligence and comments on the source of your ancestry, from the ancient one-hook, three badger in whose tender care you were entrusted.

Parade training seemed to be the "basic" in Basic Training. Wherever we went we marched, to meals, to classes, to church. We marched to the tune of "get those arms up" "get in step". "eyes front" "speak up" "pipe down" We marched with bands and without; route marches, and marches to nowhere. We nursed blisters those marches and ill fitting boots brought on; we ached in every joint, some we didn't know we had.

|

Ships

Company at Divisions |

The instructors seemed to be impervious to fatigue; they were there at dawn, they were there at nightfall. They never walked, they marched; and they always wore gaiters as a badge of office. They wore their uniforms with ever so slight violations of the accepted standards; tapes maybe two inches too long, hat tally bow an inch or two forward of what they imposed on their charges, and their collars drawn back to add a jauntiness to their attire. They maintained a steely eyed glare that must have induced eye strain. They never smiled, and they spoke in a language only time could make intelligible. The word 'attention' came out as anything from "hyaah" to "ho"; 'stand at ease' became "stundut heez"; 'left, right' became "hef tite", and so on. Once we understood them we got along fairly well, and at times toward the end they became almost genial.

Then there were the classes in seamanship taught by a crusty old Petty Officer, sometimes of R.N. origin, who probably served on the Victory with Nelson. In marked contrast to these characters were some of the junior divisional officers, who had probably joined the Navy the week before we did. They nervously watched over their charges with constrained anxiety which was replaced with undisguised relief when Divisions and Evening Quarters could actually be completed without incident. They had a consuming dread of Captain's Inspection, where anything could go wrong and usually did.

It is worthy of note that interspersed within this routine was a phenomenon known as PT (physical training) for which we were required to dress in shorts, T shirts, and running shoes, for which we were required to turn out before breakfast, and which was held outdoors only on those days when the temperature was -20 degrees or lower. With all the exercise we were already getting this seemed a bit superfluous but which we accepted along with all the other things we had learned to expect.

After about three weeks had passed and the routine became somewhat bearable there was a noticeable easing of that knot of tension that had taken up permanent residency in our midsections. Somewhere about then there was the suggestion that a weekend might be in the offing. But not before they filled you full of shots. You were vaccinated for everything and you boarded the train for home too ill to really enjoy your weekend. By the time you had recovered it was time to return. There was the question of money. Funds had a way of rapidly dwindling if and when you got paid. There were frequent visits to the canteen at meal time to buy chocolate bars to take the place of the unpalatable food; there was boot polish and kit-bag locks to buy; shaving cream and razor blades; writing pads, and envelopes, and stamps, to maintain the link with that other world you knew.

Yes, the third week was the turning point. You found you could endure the marching, the PT, and the single thud of thirty or so heels hitting the pavement together became the metronome you responded to. "You'll Get Used To It", the old song explained, and you did; you did things automatically now, responding with "sir", and saluting everything in sight to be on the safe side. There was less confusion, and you learned to sleep through just about anything, except classes of course.

In the last weeks discipline intensified; precision in everything intensified and in each of us there grew an esprit de corps, a determination to outdo the other divisions. This, of course, was instilled by every insidious and devious method our instructors might devise. We began to realize there was fierce competition among that group but by now we could all enter into the spirit of the thing. Well, nearly all; it seemed every division had an awkward squad candidate. He marched funny, was usually out of step, and came to a halt one pace later than everyone else, frequently causing a domino effect. Instructors arranged dental appointments for those chaps on "Passing Out" days.

By now you might, by some curious circumstance, find you had a Sunday afternoon to yourself to explore this town you were in. You walked, completely oblivious to having spent the last weeks marching, day in and day out. Once in a while we got to see a movie, though most of them were training films, made during WW1.

With the end of Basic Training in sight, each began to wonder how trade school would be in comparison to this labour camp we had survived. For each, in joining the Navy usually signed on for some specific trade, chosen from a list in which there were presumed to be shortages. You usually didn't have too much time to decide, maybe fifteen minutes if you were at the end of a line, and had little or no description of what was involved. But we assured each other it would be better.

Now we would go on to Stadacona, or Esquimalt, or Cornwallis; the east coast or the west coast, getting a little closer to the sea and to what we were supposed to be training for. Perhaps to the gunnery school or the torpedo school, or a technical school for engine room and stoker training, or communications at St. Hyacinthe, or perhaps directly to a ship tied up in some remote harbour.

Many went on to HMCS Cornwallis on the Bay of Fundy for further training. This base was to become the epitome of what constituted a training base. It had classrooms for everything; and was equipped with every conceivable variation of what could be expected aboard ship. (However all will recall that nothing prepared you for trying to contend with your job on the heaving deck of a warship.) Many who arrived there while it was under construction had to contend with a sea of mud, and depend on boardwalks to get from here to there. Basic Training here was exquisitely refined into the ultimate and made your first weeks in the original base something akin to a Sunday School picnic. But by now you could take it; though everyone must remember thinking "why do they do this".

Basic

Training in the Navy was an experience ... remember?

(Source: NeneLives; ed. Kenneth

Riley, ppg. 9 - 13)